Cary Sisters

‘When preparing for our first tour over Ohio we passed a few days in the rooms of Dr. Randall, Secretary of the Cincinnati Historical and Philosophical Society. The Doctor then mainly constituted the society. A few years later he was shot while dodging somewhere in California behind a counter to avoid the ire of a pursuing ruffian: but the society still survives. He had as an office mate L. A. Hine, then youthful, large and handsome, Who was trying to reform a deceptive and deceiving world by publishing a magazine called, “The Herald of Truth,” wherein was duly set forth a nice project for “Land for the Landless:” and then later he established his permanent home with his family at a spot properly named for domestic felicity; it being Love Land.

The rooms were on East Fifth street, opposite the old Dennison House, where the well-fed, portly form of Landlord Dennison, father of a then-to-be war Governor, was a daily object for pleasing contemplation. Alongside was the horse market, where for decades were daily sales of horses, sold amid crowds of coarse-grained men, unearthly, confusing yells and poundings of auctioneers, and the scampering to and fro on bareback horses of stable boys through the street to show their points. On looking upon the spot, its vulgarity and coarseness, its yells and shouting, and often oaths, it seemed as though the gates of heaven must be afar at least there appeared no one in search of them in that vicinity. To enhance the attractions it was at a time when the city was termed Porkopolis, its citizens Porkopolitans, for swine had full liberty of the streets, living upon their findings, or going in huge droves stretching from curb to curb to temporary boarding places in the suburbs on Deer creek.

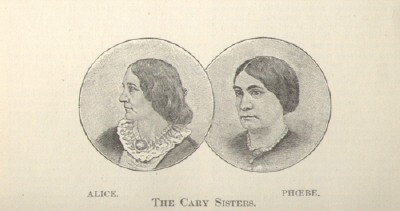

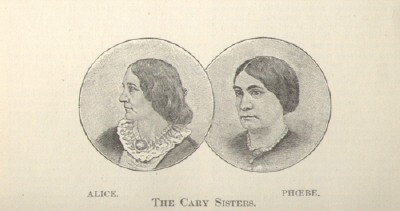

One day, while there in the rooms of the society, in bounced two laughing, merry country girls. Some jokes passed between them and the Doctor and Hine, and then they bounced out. They were from a rural spot eight miles north of the city, and well named Mount Healthy, their names Alice and Phoebe Cary, girls then respectively 26 and 22 years of age, and just rising into fame.

The portraits as published are not at all as they were then. Phoebe had a round, chubby face and seemed especially merry. Alice we again saw and but once years later at a concert by Jenny Lind in the old National Theatre on Sycamore, near Third street. She was then small and delicate with an oval face, expression sedate and thoughtful. She was attired in Quaker-like simplicity, her dark hair parted in the middle and combed smooth over the brow. No maiden could look more pure and sweet than she on that evening. Her appearance remains as “a living picture on memory’s wall.” By her sat that most superb-looking, rosy-cheeked old man, Bishop M’Ilvaiane, whose resemblance to Washington was of almost universal remark. Robert Cary, the father of the Cary sisters, came in 1803 to the “Wilderness of Ohio” from New Hampshire, and in 1814 married Elizabeth Jessup and made a home upon the farm afterwards known as the “Clovernook” of Alice Cary's charming stories.

Their mother, a sweet woman of literary tastes, died in 1835, and two years later their father married again. Alice was then 17 and Phoebe 13 years of age. Their stepmother was unsympathetic with their literary aspirations, which at this time were budding. Work with her was the ultimatum of life, and while they were willing and aided to the full extent of their strength in household labor, they persisted in studying and writing when the day’s work was done, while she refusing the use of candles to the extent of their wishes, they had recourse to the device of a saucer of lard with a bit of rag for a wick after the rest of the family had retired. Alice began to write verses at 18, and Phoebe some years after her. For years the Cincin-nati papers formed the principal medium by which they became known, then followed the Ladies’ Repository of Boston, Graham’s Magazine, and the National Era of Wash-ington. Recognition from high authorities at the East then came to their Western home. John G. Whittier and others wrote words of encouragement, and Edgar Allan Poe pronounced Alice’s “Pictures of Memory’’ one of the most musically perfect lyrics in our language, in 1849 a great event occurred to the sisters—a visit to their home from Horace Greeley. The philosopher had come to the city and wanted the pleasure of an acquaintance with these rural maidens whose simple, natural verses of country life had touched a sympathetic chord, and so went out to their home and gladdened their hearts. We presume after that visit the stepmother wished she had been less close with her candles.

We remember that time well; the philosopher was an old acquaintance; the weather had turned intensely cold, and he said to us he was unprovided with a sufficiently warm clothing for a return by stage coach over the mountains.

A winter fashion at that time in the Ohio valley was a huge coarse blue blanket with a black border of about six inches. These shawls were extensively made into overcoats, whereon their black zebra-like stripes had full display. A more uncouth appearing garment could not be well imagined either as a shawl or overcoat. It was warm, but absorbed rain like a sponge. The shawls had struck the philosophic eye, they were so pe-culiarly what was then known as “Western,’’ and to an inquiry we replied we had one not in use to which he was welcome. He gratefully accepted the gift and wore it home as a specimen of Cincinnati fashions, carrying, too, in its meshes a generous quantity of the city’s soot, for which the garment had an especial retaining adaptability. To have thus ministered in that long ago to the comfort, of an old-time philosopher bent on reforming mankind and inviting young men ‘‘to go West” is another pleasuring picture on “Memories walls.” Nearly thirty years elapsed ere we again saw the sage— he was on his Presidential canvass, riding through Fourth Street in an open barouche. His white benevolent face had broadened, and he was bowing and smiling to the people looking “for all the world” like some good old grandmamma when bent on dispensing to the youngsters some good warm gingerbread just out of the oven.

Having obtained recognition from the East literary and some pecuniary success by a volume of their poems, in 1852, the sisters, first Alice and then Phoebe Cary, remove to New York to devote themselves to literature. They established themselves in a modest home, and by their habit of industry and frugality had success from the very start.

Occasionally they visited their old home and resumed the habits of their girlhood days. When they had obtained literary eminence they established on Sunday evenings weekly receptions, when for a term of fifteen years were wont to gather the finest intellects, the most cultured characters of the metropolis and the East. Assemblies so comprehensive in elements, so intellectually varied and harmonious, were never before seen in the metropolis. They were quite informal and not especially gratifying to the mere butterflies of fashion whom curiosity sometimes prompted to attend.

Alice was frail, and in her last sickness, prolonged for years, she was tenderly nursed by her stronger sister, bearing her great sufferings with wonderful patience and resignation. Alice died February 12, 1871, and five months later Phoebe followed her. She was naturally robust in health, but she had been weakened by intense sorrow, and then becoming exposed to malarial influences quickly followed her sister. Both were buried in Greenwood cemetery.

It had been pitiful to see Phoebe’s efforts to bear up under her dreadful loneliness after her sister’s death. She opened the win-dows to admit the sunlight, she filled her room with flowers she refused to put on mourning and tried to interest herself in gen-eral plans, for the advancement of woman. All in vain. Her writings were largely poems, parodies and hymns.”

One of her poems, written when she was only eighteen years of age, has a world-wide reputation. Its title is “Nearer Home,” and it has filled a page in nearly every book of sacred song since its composition. Its opening verses are:

On sweetly solemn thoughComes to me o’re and o’re:I am nearer home to-dayThat I ever have been before.Nearer my Father’s houseWhere the mansions be;Nearer the great white throne,Nearer the crystal sea.

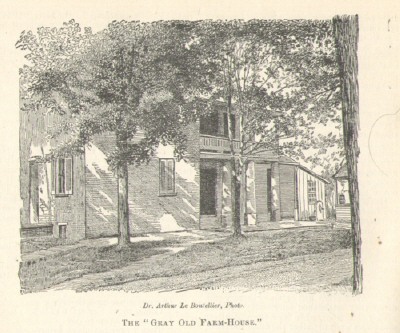

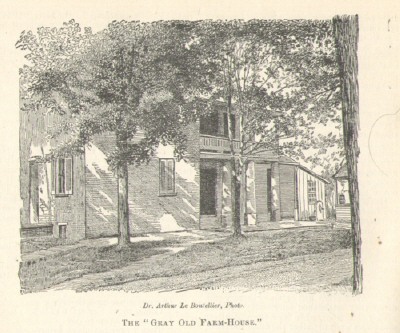

The Cary Homestead, “the old gray farm-house,’’ is still standing, in a thick grove about 100 feet back from the road, on the Hamilton pike, just beyond the beautiful suburb of College Hill, eight miles north of Fountain Square. The sisters were born in a humble house of logs and boards on a site about a hundred yards north of it. It is of brick, was built by their father about 1832, when the girls respectively eight and twelve years of age. It is a substantial, roomy old-fashioned mansion, and is just as the sisters left it when they went to New York to seek their fortune. It has many visitors attracted by memories of the famous sisters, a brother of whom, Warren, a farmer, still lives there. After their decease Whittier, in writing of their original visit to him thus alluded to it:

Years since (but names to me before)Two sisters sought at eve my door,Two song-birds wandering front their nest,A gray old faint-house in the West.Timid and young, the elder hadEven then a smile too sweetly sad;The crown of pain we all must wearToo early pressed her midnight hair.Yet, ere the summer eve grew long,Her modest lips were sweet with song;A memory haunted all her wordsOf clover-fields and singing birds.

One of the attractions of the region is the old family graveyard.

The most interesting single object in this region is what is known as “the Cary tree,’’ It is the large and beautiful Sycamore tree on the road between College Hill and Mount Pleasant. The history of this tree is very interesting, as given by Dr. John B. Peaslee, ex-superintendent Cincinnati public schools.

In 1842, when Alice was twelve years old and Phoebe only eight, on returning home from school one day they found a small tree which a farmer had grubbed up and thrown into the road. One of them picked it up and said to the other: “Let us plant it.” As soon said these happy children ran to the opposite side of the road and with sticks—for they had no other implements—they dug out the earth, and in the hole thus made

they placed the treelet around it, with their tiny hands, they drew the loosened mold and pressed it down with their little feet. With what interest they hastened to it on their way to and from school to see if it were growing and how they clapped their little hands for joy when they saw the buds start and the leaves begin to form! With what delight did they watch it grow through the sunny days of summer! With what anxiety did they await its fate through the storms of winter, and when at last the long looked-for spring came, with what feelings of mingled hope and fear did they seek again their favorite tree.

When these two sisters had grown to wo-manhood, and removed to New York city, they never returned to their old home with-out paying a visit to the tree that they had planted, and that was scarcely less dear to them than the friends of their childhood days. They planted and cared for it in youth they loved it in age.

Mr. Peaslee was the first person anywhere to inaugurate the celebration of memorial tree-planting by public schools, which he did in the spring of 1882 having the Cincinnati schools plant arid dedicate with mu-sical, literary and other appropriate exercises groups of trees in honor and memory of eminent American authors. The grove thus planted is in Eden Park and is known as “Authors’ Grove.’’ At that time the above description was used as part of the exercises around the Cary tree, planted by the Twelfth district school of the city.

The school celebration of memorial tree-planting was the outgrowth of the celebration of authors’ birthdays, which had been in-augurated by Mr. Peaslee in the Cincinnati schools some years previously. He had simply carried the main features of authors’ birthday celebrations into Eden Park and united them with tree-planting.

The planting of trees and dedicating them to author’s, statesmen, scientists and other great men have from this Cincinnati example been adopted by public schools in nineteen States of the Union, the Dominion of Canada, and the beautiful custom has crossed the ocean to England, and as a consequence millions of memorial trees have been planted by school-children.

From Historical Collections of Ohio by Henry Howe; Pub. 1888